A few years ago, in a class for teenagers on how to read the Bible, I showed them Hosea 1:2 — “Go, marry a promiscuous woman….” I asked them how that applied to us today, and how we were supposed to obey that command. And I got, as I had hoped, some blank stares and a few uncomfortable chuckles.

Hosea’s actually easy; the text itself gives hints to who it was for. It says that these are God’s words to him — to Hosea, that is. It is a command from God, but it’s to Hosea.

The second major hint to reading the text is what God says after the command: “…for like an adulterous wife this land is guilty of unfaithfulness to the LORD.”

So this command isn’t to us, and it isn’t about us. It’s a command given to an Israelite prophet who lived nearly 3,000 years ago. It’s intended as a sort of acted parable about the broken relationship between Israel and their God. It was written down by the prophet or his disciples, and later regarded as Scripture by Jewish people, some of whom several centuries later became Christians and shared those Scriptures with non-Jewish people.

So, how is it Scripture to us? Well, we can see what it says about human beings. In what ways have we broken faith with God? What “adulteries” do we pursue? Have we ever even thought of sin, particularly idolatry, as “adultery”, breaking faith with God?

But we should also ask what this text tells us about God. He’s heartbroken. He’s hurt when we break faith with him. But he doesn’t give up on us. As you read on, you see a God determined to win his people back to him. He’s going to “lead [Israel] into the desert” — exile — but with the intention of renewing the covenant. He doesn’t believe his people are too far gone that they won’t see what they’ve done and return to their God.

It isn’t hard, as Christians living more than two thousand years later, to make the connection to the story of Jesus: God doesn’t give up, he pushes past the limits to bring his people back to him.

See what we did? We read that text by looking at what’s still the same — a God who doesn’t change, and flawed human nature — to make comparisons and connections. It’s another example of “covering” a text.

We often just ignore books like Hosea, where the distance seems too great. That’s one of the reasons we end up with a “canon within a canon” — something we’ll get around to talking more about. We shouldn’t ignore them. We just shouldn’t treat them like they’re written directly to us.

One thing you might have noticed is that the interpretations I’ve suggested don’t come from that five word command, “Go, marry a promiscuous woman.” Part of our problem in reading Scripture is that we try to find commands or inspirational verses to just apply directly to ourselves because that’s easier.

But here’s what I want you to know: there is not one word in Scripture that is written directly to us.

Not one? There are some that feel so immediate. “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” But, who’s God? And who’s this Son? Belief takes some unpacking, doesn’t it? Most of those connections we make unconsciously — but they connect to other times, other places, other people. God does love us, and he loved us by giving his Son for us, and through him eternal life is for us. But even that text wasn’t written directly to us.

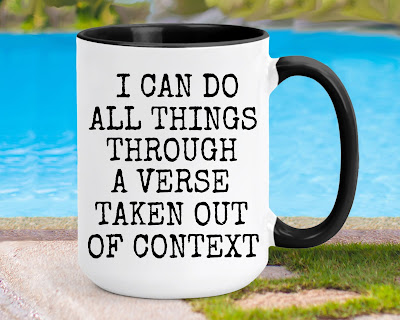

Or take Philippians 4:13 — “I can do all things through him who strengthens me.” I have a photo of a mug that says, “I can do all things through a verse taken out of context,” and that sums up our mistakes with this text. Paul wrote those words about himself. He was talking about enduring deprivation and need in prison. We sometimes think that verse is telling us that through Jesus we can have everything we want, but for Paul it was the secret of his contentment in circumstances he didn’t want! It has something to say to us, for sure — but it’s not that if we just believe hard enough Jesus will give us that seven-figure income! It’s that we can be content with having less than we want or even need through the strength Jesus will give us.

It matters; Interpreting Philippians 4:13 like we often do can devastate people who are struggling by making them think there’s something wrong with their faith. We can do such damage when we read the Bible like it’s primarily to us.

Take 1 Corinthians 14:34 — “Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says.” Well, what law says that? Probably it refers to the Old Testament, though there are no laws that say that in so many words. In any case, when we read this text like it’s written directly to us as a sort of worship service owner’s manual for all time, we miss some things.

First: Paul’s addressing a specific problem in the church in Corinth in his day. Their gatherings are a chaotic mess, with people trying to speak in tongues and prophesy over each other. Paul says that God doesn’t create confusion, so if he inspires a prophet while another prophet is speaking that means it’s time for the first prophet to “be silent.” And women in Corinth, who were interrupting to ask questions of the prophets, needed to “be silent” and ask their husbands at home.

Second: He’s already written guidelines for women who pray and prophesy. Complete silence of women in all or even most contexts wasn’t required. Women prophesied and prayed, and there’s nothing to suggest that it wasn’t in the context of the church assembled together.

Third: He writes that “It’s disgraceful for a woman to speak in church.” He doesn’t qualify this in any way, but the disgrace he mentions has to do with his culture, in which women didn’t have equal public standing with men. Once again, it wasn’t written directly to us.

And again, this text has authority for us. But it’s not something we should obey by copying directly. And we know that, don’t we? We don’t require women to cover their heads in our assemblies, or think it’s “disgraceful” (11: 6, same word) if a woman cuts her hair short. We don’t require a “holy kiss” at church. First Corinthians was written to people for whom a kiss of greeting, head coverings for women, and yes, submission represented by silence in gender-mixed public places was normal. Unless we’re ready to say that to be faithful we have to reconstruct first-century Greco-Roman culture in its entirety (hello, holy kisses), we have to recognize that interpreting Scripture isn’t as simple as arbitrarily assuming that some texts can be applied directly to us while others can’t.

Reading the Bible this way will sometimes yield different results among different people. Some latitude has to be given for differing understandings of a text. Listening and humility will be required.

That’s OK though. Listening and humility should be two traits that every follower of Jesus is cultivating.

Which might remind us that, as we’ll talk about in the next post, interpreting the Bible is something we do not just with our intellect, but also with our character.