…I will return and rebuild David’s fallen tent. Its ruins I will rebuild, and I will restore it, that the rest of mankind may seek the Lord, even all the Gentiles who bear my name…

-James, Acts 15:16-17, quoting Amos 9:11-12 (NIV)

In church a week or two ago, singing one of the songs that we only sing around Christmas, a thought struck me. Maybe it’s occurred to you, too, and if so then maybe you’ll be interested.

We were singing The First Noel. Now, I have to say, this is not one of my favorite songs of the season. It sounds pretty enough, I suppose, but it’s a little repetitive, its language is awkward, and it rhymes are clunky. But as we sang it this year, it was the refrain that stood out to me:

Noel, Noel, Noel, Noel,

Born is the King of Israel.

Isn’t that odd that we get together on Sunday mornings and sing hymns about the King of Israel? Isn’t it odd that we commemorate his birth every year? I mean, we wouldn’t think of doing that for a king of Spain, say, or a Roman Emperor. For some reason, though, the fact that Jesus is the King of Israel is still acknowledged in the Scripture and music that’s meaningful to us — the huge majority of whom are non-Jews — during Christmas.

It’s true that, as Christianity became disconnected from its Jewish moorings, the kingship of Jesus has also been unmoored from Judaism. It does’t sound strange to describe Jesus as “king of kings,” or “king of the world,” or even, personally, “my king.” But now and then, whether in a couple of Christmas songs or peeking through the New Testament, we still refer to Jesus as “King of Israel” or “King of the Jews.”

So maybe you’ve noticed this before, and you’ve asked, “Why?”

Let me see if I can get across why it matters that Jesus is the King of Israel. Not that he isn’t King of Kings. Not that it isn’t appropriate for you to think of him as your King, and yourself as his subject. But I want to try to tell you, if you don’t already know, why we should still see him as the King of Israel. And you may not know, because it’s something that the church, in our desire to communicate the gospel to non-Jewish people, has sometimes put aside as unimportant and irrelevant.

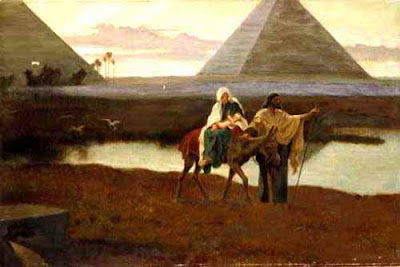

In response to that impulse, let me remind you that the Magi in Matthew came to worship Jesus because he was to be King of the Jews. He wasn’t going to be the king of their country. But somehow, through their astrology, God communicated that this King of Israel would be significant to them, too — significant enough that they should go on a long and dangerous journey to honor him.

Throughout all four Gospels, Jesus is referred to constantly as the King of Israel, the King of the Jews, and the son of David. Both Peter, in Acts 2, and Paul, in Acts 13, preach that Jesus was a descendant of David and thus heir to David’s kingdom. In 2 Timothy, Paul urges Timothy, “Remember Jesus Christ, raised from the dead, descended from David. This is my gospel…” It was part of the gospel that Paul, the apostle to the Gentiles, preached that Jesus was the Messiah, the King of Israel from David’s line, who would come to save his people. Twice in Revelation, Jesus is called “the Root of David,” emphasizing that he is Israel’s rightful king. The New Testament won’t let us overlook the fact that Jesus was the King of Israel.

The reason it remained a part of the early church’s gospel, even as the good news of Jesus spread into non-Jewish places and among non-Jewish populations, is that it isn’t just about the usual politics and dynastic succession. The King of Israel was an idea full of controversy, expectation, and most of all hope. The word Messiah just means “one who’s anointed” — like a king was anointed. The one who would save Israel from its enemies and deliver its people a time of unprecedented prosperity, peace, and security would be a king.

But that doesn’t exactly answer our question, does it, about why it still matters to non-Jewish people two millennia later that Jesus is the King of Israel?

Well, very simply, the coming of the King that would save Israel was always supposed to have implications for the whole world. Listen to these texts about the time of the Messiah:

“Many peoples and the inhabitants of many cities will yet come, and the inhabitants of one city will go to another and say, ‘Let us go at once to entreat the LORD and seek the LORD Almighty. I myself am going.’ And many peoples and powerful nations will come to Jerusalem to seek the LORD Almighty and to entreat him.” (Zechariah 8:20-22)

Many nations will come and say, “Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the temple of the God of Jacob. He will teach us his ways, so that we may walk in his paths.” The law will go out from Zion, the word of the LORD from Jerusalem. He will judge between many peoples and will settle disputes for strong nations far and wide. They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore. Everyone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree, and no one will make them afraid, for the LORD Almighty has spoken. (Micah 4:2-4)

There’s this from Isaiah, about the “chosen one” from Israel who God delights in and on whom he will put his Spirit:

I will keep you and will make you to be a covenant for the people and a light for the Gentiles, to open eyes that are blind, to free captives from prison and to release from the dungeon those who sit in darkness. (Isaiah 42:6)

Those three are just a small sample, but maybe enough to make the point; the Messiah, the King of Israel expected to come and save his people, would also be the Savior of the world. Nations would come to him to learn the ways of God. Disputes would be settled, war as a way of expanding and finding security would end, because everyone would have plenty. The Messiah would be a light for all nations, freeing them from darkness and captivity.

In Acts 15, James explicitly connects what he sees happening in the growth of the gospel among the Gentiles with the Old Testament expectation that God would “rebuild David’s fallen tent.” James believed that’s what he had done in Jesus.

This is why it matters still that Jesus is the King of Israel. This is why it should still matter to us, spiritual heirs to the promise of the prophets and the fulfillment of their prophecies that Jesus, the King of Israel, would be a light for the Gentiles.

May we share that light with a dark world. May we be those who invite others from among all nations to “go at once to…seek the LORD Almighty.”

Born is the King of Israel.

Let’s never stop singing that song.