There’s a country song that’s been getting a lot of attention lately — negative attention, though it’s also number one on the Country charts. Which just goes to show that, up to a certain point, it’s true that there’s no such thing as bad publicity. I really don’t want to bring the song even more attention from the tens of people who read my scribblings, so I’m not going to name it or link to it. Likely you already know the one I’m talking about. Given its title, people who live in Chicago aren’t exactly its intended audience, so I’m sure it doesn’t bother anyone associated with it that I don’t care for it. (It turns out I went to high school with one of the writers, who I always liked. So, you know, nothing personal.)

That said, I agree with a lot of the criticism leveled at the song. It talks about how in small towns, people “take care of our own,” and if you “cross that line”…well, it’s kind of non-specific as to what happens, but it has to do with “good old boys.” It’s a song that appeals to all the worst instincts of human beings. It’s about taking matters into our own hands when “lines” are “crossed” and “our own” are threatened.

Well, taking matters into our own hands is exactly how some of the worst atrocities in human history came about. We can’t be trusted to draw “lines” in the right places. And we definitely can’t be trusted to define “our own” properly.

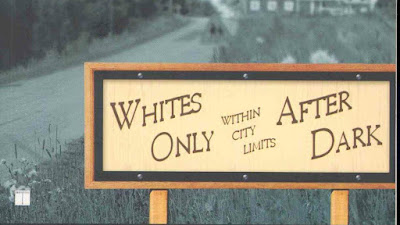

Every town in America, small and large, has stories about what happens when lines are crossed and we take care of our own. There were at least 5,000 “sundown towns” in America, where Black people were not allowed after sundown. Some of those towns had ordinances still on the books into the 70s and 80s. “Our own” almost always has very specific connotations, full of racial, gender, religious, and ethnic prejudice, sometimes not even consciously articulated. (We just know when someone is “our own” and when they aren’t.) When a Black man was lynched in a small town, or when a Chicago gangster fires into a crowd with the intention of killing somebody affiliated with another gang, when a bunch of “good old boys” in a small town roughs up a trans woman or a neighborhood is redlined in a large city, it’s the same problem, isn’t it? We’re fine with some lines getting crossed; in a lot of places, small and large, a White person can get away with a lot more disrespect to a police officer than a Person of Color can. It’s all about who is “our own,” and who’s not. It’s all about who decides which lines can’t be crossed by whom.

Maybe — hopefully, surely — the songwriters didn’t intend all that. But, be assured, that’s what people hear. And that’s at least part of the reason the song is so popular. Its sentiments are a dog whistle for some of the least admirable qualities of human beings, wherever they might live. If you feel like whatever lines you’ve drawn are being crossed, like your “own” are threatened, this song validates those feelings. It appeals to fear, anger, bitterness, victimhood. If you like the song, ask yourself honestly why. What does it say that appeals to you? You don’t have to justify it to me, of course not. But when you hear about lines being crossed and “our own,” what comes to mind? And what should be done about it?

Even in the song, the “lines” that shouldn’t be crossed kind of blur. Flag-burning, which is legal, is included with assault, carjacking, armed robbery, and spitting on a police officer — which, are not legal, let’s see…anywhere. No one, whether you live in New York City or Bucksnort, Tennessee, thinks any of those things are OK. (Not even the people who commit those crimes.)

I think the flag lyrics are actually about public demonstration and protest, which, if I remember correctly, is part of my Constitutional right to peacefully assemble. I can burn a flag a day for the rest of my life if I’m so inclined (I’m not), and there’s not a boy, however good or old he may be, who should feel justified in trying to stop me. Sure, sometimes demonstrations and protests annoy and anger us — but isn’t that the point of a protest? To draw attention to some injustice by shaking us and disrupting life as usual?

But, see, that’s what happens when we draw and police our own lines. We keep drawing them tighter and tighter. Until before you know it, the only “our own” worth fighting for are those who think, act, and speak just like me, who protest only what I already hate and value the same symbols I value. The song offers a “might makes right” view of the world, where nearly anything I have the strength to do to police the lines I’ve drawn and take care of my own, however narrowly defined, is acceptable.

Well, let me offer an alternative point of view.

Jesus didn’t distinguish between “our own” and everyone else. He was the victim of vigilante justice and state-sponsored assassination, and yet as he died he didn’t call “his own” to take matters into their own hands. He prayed for the forgiveness of his murderers. He called his followers to the kind of love that crosses lines and extends far beyond “our own.”

He told a story once, a story we call The Good Samaritan, in answer to a man who asked who he should regard as his “neighbor.” This man wanted to know who his neighbor was because he knew the Scriptures told him he was to love his neighbor as himself. A love that all-consuming — well, it’s reasonable to ask how many people you’re on the hook to love that way, right?

In the story, a man was robbed and beaten. A Priest and a Temple worker, who Jesus’s hearers might have expected to stop and help, cross to the other side of the road to avoid helping. The one who stops is a “Samaritan” — an ethno/religious group many people listening to Jesus would have looked down on.

Jesus drives home the point of the story when he asks, “Who was a neighbor to the victim?” He turns it around. This guy just wants to know who his neighbor is. Jesus reframes the question: “Who was a neighbor to the one in need?” Neighbor isn’t a noun. It isn’t a matter of drawing lines and deciding who fits within them and who doesn’t, who qualifies to be called “our own” and who deserves to be regarded with suspicion or hostility. “Neighbor” is a verb. It doesn’t ask us to draw lines and cross the street; it draws us out of our comfortable places to give, to sacrifice, to put ourselves on the line for other people. Jesus’ view of the world challenges us to love our neighbors as ourselves, and defines our neighbors — our own — as every person we have the opportunity to love and care for.

Here’s a question: If Jesus told the story to us today, who would he say stopped to help, and who would he say passed by on the other side of the road? A Democrat? A Republican? A Black man? A Latino teenager? A wealthy person? A poor person? A single mom on welfare or a “Karen”? Someone from a big city, or a small town? A Christian, Muslim, or Jew? A Central or South American immigrant?

How we answer that question might say something about how we define “our own” too narrowly.

We’re wasting a lot of time and energy if we’re worried about policing our lines and defending our own. That will shrink your world down to little more than a tiny circle with you alone in the middle. Jesus calls us to more than that. Who is your neighbor? Not “your own” — your neighbor.

To whom will you be a neighbor going forward? Who will you reach out to help, serve, and care for? Make it someone who you wouldn’t have imagined helping before. Or who you never imagined would help you.

Try that in a small town. Or a big city. Or anywhere in between. See what happens.