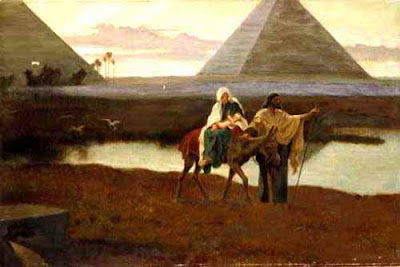

…[A]n angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,” he said, “take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him.”

-Matthew 2:13 (NIV)

The part of the Christmas story that never gets represented on cards or Christmas decorations is one we need to talk about. Just because Linus didn’t quote it in the Charlie Brown Christmas Special doesn’t mean we should ignore it. In some ways, it’s the part of the story that rings truest to life.

King Herod — called “the Great” because of his building projects — elected to massacre the children of some of the people he ruled rather than risk losing his and his family’s claim to the throne to some newborn Messiah.

Even in our world, jaded as it is by constant media coverage of every atrocity ever committed by any government, Herod’s actions stand out. It’s directed, surgical in its precision: he had every boy in Bethlehem two years old and younger murdered. Like every tyrant before and after, his interests came before the loss of innocent lives. His and his family’s future had to be secured at any cost, even at the cost of anyone else’s.

Not the first time, or the last. The Rohingya in Myanmar. Blacks in apartheid South Africa. Kurds in Turkey and Iran. Indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand. Jews in many countries throughout the world. Christians, Hindus, and Muslims in many places. All have suffered at the hands of oppressive governments more interested in their own prosperity than in the well-being of human beings who have done nothing wrong.

Ah, but we don’t have to go too far away or too far back in time to see it, do we? American expansionist dreams displaced indigenous populations from sea to shining sea. People kidnapped from their homes across oceans and bought and sold and worn out and discarded as property built much of what we take for granted. When Black people cried out for justice in the Jim Crow era, they were systematically put down by a government unwilling to listen to them. By and large, those in power are invested in keeping things at status quo, and they can justify whatever they need to justify to make that happen.

Mary, in her song in Luke that we looked at last Sunday, sings about a God who “has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble.” When government prevents or obstructs the flourishing of human lives, she says, God brings them down. In their place, he raises up those in humble circumstances, the ones previous administrations ground under their bootheels. This was true in her own life; God brought his people’s Savior to them through her, a young woman in a “humble state.” The birth of Jesus is about that reversal, about the ways God works to raise up the humble and bring down those in power. Jesus’ first skirmish with the authorities shortly after his birth foreshadowed the antagonism of the religious authorities and his final confrontation with religious and civil authorities at his trial and execution. When the Roman governor put The King of the Jews on his cross, he didn’t know what he was saying. But he was right. Jesus was taking his throne.

Our nation, like many before it, cloaked our national goals in religious terminology. That made it easier for us to convince ourselves that we were on the side of right: “civilizing” those “savage” indigenous people, for instance, or that we were benevolent slave owners who improved the lives of the human beings we forced to work for us. White religious leaders in the south conflated the goals of the civil rights movement with “Godless Communism” as an excuse to oppose them.

All of that should remind us that authority can’t be trusted, that it will always defend its own interests at the expense of people it has injured and broken, and that religious terminology and ideals often make the best stealth technology to hide its true motives.

In my Harding University alumni magazine for Fall 2021, there’s a cover story about Elijah Anthony and Dr. Howard Wright, who in 1968 — as it happens, the year I was born — became the first African-American students to earn bachelor’s degrees from Harding. At Homecoming this year, Harding renamed the building we always called “The Administration Building” “The Anthony and Wright Administration Building.”

The Administration Building. I never noticed anything in the article acknowledging the fact that it was The Administration that kept Harding segregated until 1963, in spite of student, alumni, and faculty calls for integration long before then. Or that the date of Harding’s integration coincided suspiciously with the Civil Rights Act, which removed access to federal funds from any college or university that remained segregated. Which might make cynical people wonder about the university’s motives.

I’m thankful that Mr. Anthony and Dr. Wright were acknowledged. I wish some of the students denied entry to Harding through the years because of the color of their skin, some who I know personally, had also been acknowledged in some way. Along with the evil of an administration that kept Black students off the campus of a university that they called “Christian.”

But I wonder if back then I would have been able to see through the rationalizations justifying segregation to the real reasons — that people in authority had stuff they wanted to defend, and that they’d do what they needed to do and advocate what they needed to advocate to make sure it was defended.

How do we respond today when people raise their voices and cry out for justice? Do we look the other way? Do we look for conspiracy theories and draw false equivalencies to justify doing what’s necessary to quiet those voices? Do we trust in “authority,” even though we should know full well that authority has its own agenda?

That last one is the temptation for me, I think, as a white man who has often been well-served by the other white men who have usually wielded that authority. I haven't felt its knife edge. Often, their agendas suit me, too, in the short term at least. And so maybe I’m more inclined to take their rhetoric at face value and trust their systems instead of hearing the genuine voices of people in need of justice, righteousness, compassion, and mercy.

We wear the name of a Savior, however, who from the beginning proclaimed a kingdom that was in opposition to earthly authority. He taught us how to fight it, too, with a power “not of this world”: by loving and caring for “the least,” by inviting the poor and humble to our tables, by turning the other cheek to authorities so incensed by Jesus’ kingdom that they’d slap us in the face. He taught us to look for ways to serve instead of looking to be served. He taught us to find glory in humility and distrust the prideful and arrogant. He taught us not to let fear for our own well-being get in the way of offering ourselves, and he taught us to forgive those in power who would harm us for following him instead of going along with them.

He taught us that no authority — civil, religious, or otherwise — takes precedence over the kingdom he came to open to all people.

I’m reminded of the late Representative John Lewis’ famous quote: “Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” When we refuse to go along with authority guarding its own agenda by trampling others, we might find trouble. But we’ll never be more like Jesus.

I know, that doesn’t make as catchy a tune as Deck the Halls. Still, that is Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment