Hopefully, you’re getting the idea that reading the Bible is not just a matter of opening it up.

Interpretation is required. It can be hard work. There are matters of translation to deal with. There are the problems we’ve already considered: How sometimes the Bible is read and applied absent character, that the Bible wasn’t written to us, and how reading the Bible can become a kind of groupthink that doesn’t admit alternative points of view (here and here). Reading the Bible can be hard work. But that’s not to discourage you from trying; there are measures that we as readers can take that will make things easier.

Interpretation is required. It can be hard work. There are matters of translation to deal with. There are the problems we’ve already considered: How sometimes the Bible is read and applied absent character, that the Bible wasn’t written to us, and how reading the Bible can become a kind of groupthink that doesn’t admit alternative points of view (here and here). Reading the Bible can be hard work. But that’s not to discourage you from trying; there are measures that we as readers can take that will make things easier.

One of those measures is something that we do almost unconsciously with everything we read; we take into account exactly what kind of literature we’re reading. We don’t read a letter, a poem, a grocery list, and a novel in the same way. A math textbook isn’t the same thing at all as a “how-to” book on gardening or a devotional book on prayer. We recognize without even consciously thinking about it that there are differences in how we read those various kinds of literature, even though the basic skill set is the same — recognizing words and sentences and paragraphs and connecting them in our minds with vocabulary and syntax that we know they represent.

Where the Bible is concerned, though, we sometimes forget this basic rule. After all, we believe that the whole Bible is from God and has authority for us. We may have been trained to read the Bible without regard for the kind of literature we’re reading by well-meaning preachers and teachers looking to pull a simple life lesson out of every nook and cranny of Scripture. Also, the Bible seems to be one book. But don’t be fooled; the Bible is made up of at least 66 different books, and those books represent many different kinds of literature.

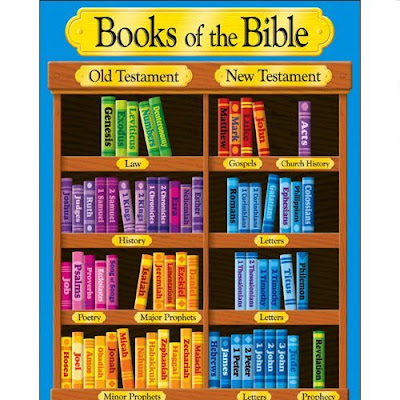

I can remember as a kid in a Sunday School class seeing a poster very much like this one that classified the books of the Bible into categories: Law, History, Poetry, Prophets (Major and Minor), Gospels, Church History, and Epistles (which I would later learn meant “letters”). That was probably my first exposure to the idea that there are different kinds of books in the Bible.

But even that doesn’t tell the whole story, does it? There is law code in the the first five books of the Bible, but there is also narrative, poetry, genealogy, and other genres that aren’t even represented on the graphic. The category of “Prophets” isn't all that helpful, because those books contain many different types of literature themselves. (In fact, most of the prophetic books could just as easily be categorized as poetry.) Gospels contain narrative, teaching, parables, and poetry as well. To categorize Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon as just “Poetry” doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of how they connect to well-known Ancient Near Eastern genres like Wisdom Sayings, or, in the case of the Psalms, that the poetry is intended for use in worship.

And what I didn’t think about when I first saw that graphic, and what many readers of the Bible never seem to consider, is that there are different ways of reading each of these types of literature.

As an example, take Psalm 139:13-14, which says, “For you created my inmost being / you knit me together in my mother’s womb. / I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made….” The slashes in that quotation represent line breaks; the text is written in Hebrew poetry, in which ideas (and not necessarily sounds) “rhyme.” The first two lines of the quote develop the same idea, with the third line springing off from the first two.

The psalm begins with a reflection on how God “knows” the psalmist. The quotation makes the point that God has known him intimately since before his birth, when God was “weaving him together” in his mother’s womb. That’s a lovely thought, a beautiful piece of poetry, that emphasizes how God knows us deeply and thoroughly and that we can’t — and don’t have to — hide from him.

Just a few lines later, you have this: “My frame was not hidden from you / when I was made in the secret place / when I was woven together in the depths of the earth.” So does God weave babies together in the womb, or in the depths of the earth? Maybe that’s just a euphemistic way of referring to the uterus. Maybe it reflects a documented belief in the Ancient Near East that embryos had their origins deep beneath the earth’s surface. There are Egyptian and Sumerian stories about gods “knitting” babies in their mothers’ wombs. And of course no one thinks God literally creates human babies with a loom!

The poetry in the Psalms doesn’t have to be literal to be true. We can thank God for our children while also recognizing that there is science behind conception that a culture without knowledge of cells would have no reason to be aware of. Infertile couples can pray for children while also being treated by a fertility specialist without being afraid that they’re contradicting their faith. A poem isn’t a textbook on conception.

Sometimes believers have drawn lines in the sand over Genesis’ account of a 6-day creation, and said if you don’t believe in the literal truth of that account then you don’t believe the Bible. That can give kids a lot of problems when they learn more scientific views of the origin of the Earth and can’t quite reconcile those views with what they hear in church. They may feel that they have to choose one or the other. (I know I struggled with that at one point in my life.)

Actually, though, the Genesis accounts of creation, the fall, and the flood sound much like Ancient Near Eastern origin stories like Gilgamesh and Atrahasis. It sounds as though Genesis is reimagining those stories with a monotheistic perspective — one God, who is faithful, generous, and patient contrasted with the gods of the pagan stories who are petty, duplicitous, greedy, and vengeful. In the Ancient Near Eastern stories, human beings are the heroes; in Genesis, God is.

If we believe that the Holy Spirit is behind these “rewrites,” that shouldn’t bother us too much. The stories are true — “God created the heavens and the earth” — even if they’re not literal. Genesis isn’t intended to be a science textbook, and shouldn’t be read that way. It works in the way parables work: communicating truth in non-literal ways.

Speaking of parables, one of Jesus’ is easy to read wrongly as well. It’s found in Luke 16 and is usually known as the parable of The Rich Man and Lazarus. Some readers don’t consider it a parable, but that’s largely because Lazarus is named. (None of the characters in Jesus’ other parables are.) However, it has all the other markings of a parable, and the fact that Lazarus is named, while the rich man is not, fits with the parable’s theme of reversal.

I’ve heard this parable used to illustrate all sorts of fanciful views of the afterlife, but of course parables don’t work that way. The Good Samaritan isn’t about how best to treat wounds. The Prodigal Son isn’t a manual on how to plan a welcome home party. The Rich Man and Lazarus isn’t a literal description of the afterlife; it’s about listening to Scripture’s commands to care for the poor in this life, anticipating the reversal that otherwise will take us by surprise in the next. It uses a well-known Jewish view of the afterlife to make this point. (The Greek word for the place where both the rich man and Lazarus are after death is Hades, which is a translation of the Hebrew word Sheol, the grave, the place of the dead.)

You may differ about some of the specifics I’ve mentioned here; that’s fine. The point to repeat is that the many different kinds of literature in the Bible demand different ways of reading and interpreting.

In the next post, we’ll look at an unusual kind of biblical literature, best represented by the book of Revelation, and some of the reading challenges it poses.

No comments:

Post a Comment