I came across a really interesting story this week, one that has some personal relevance for me, as well.

The story was about a woman named Stacie Marshall, who lives in a town called Gore, Georgia, just a hop, skip, and jump away from Chattanooga, Tennessee, where I grew up. Stacie moved back to Gore to work the family farm a few years ago, a farm that five generations of her family have tilled and harvested.

Cleaning out her grandparents’ home in 2020, she came across a piece of paper that turned out to be a record of the slaves that had been owned by members of her family. She considered just trying to forget that she had ever seen the document, but she realized that many families had been in Gore for multiple generations. She realized that some of the descendants of the slaves who had worked her family’s farm might live in the area.

The records didn’t include the names of any of the enslaved people, just genders and ages. She had no idea where to start researching who they were, or if they had descendants around. But then she remembered something from a few years earlier, when she was having trouble nursing her first daughter. Her grandfather had said to her, “That’s a trait of Scoggins women…That’s why they bought that wet nurse, Hester, to nurse my great-grandfather.” He had been told that Hester had been “like family.” Stacie had put it out of her mind. But now she had a name.

One of the enslaved people on the record was a woman, 34 years old. Stacie figured that was Hester. Post-war census data confirmed that a woman named Hester Scoggins who would have been the right age was still living in the area. She took that name to a childhood friend of her father, Melvin Mosley, and his wife, Betty. They were gratified that Stacie was interested in finding out more. They prayed that God would use her efforts to break generational sin, and that Stacie’s farm would be a place of love for the community.

In July of 2021, in a New York Times piece on her story, Stacie said, “This is something I will live out for the rest of my life. I want to do what Melvin and Betty charged me with, to use this farm as a way to tie our community even closer. That won’t ever be truly finished.”

Then a few months later, something really amazing happened: A local historian figured out that Betty Mosley’s great-great-grandmother was Hester Scoggins. Now Betty and Stacie host college groups at the farm. The students take an experiential farm tour, eat the Mosley’s barbecue, and listen to Betty and Stacie talk about their families’ intertwined history. None of which would have happened if Stacie Marshall had just closed the drawer on that slave record and an uncomfortable fact of her family’s legacy.

As I read that article this week, the Florida Board of Education was approving a new set of curriculum standards that, among other things, require instruction for middle school students that includes “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.” In other words, students have to learn about how Black people benefitted from slavery. (In case you’re wondering, that will be a very short chapter in the textbook.) The Board also rejected a proposed Advanced Placement course in African-American History, claiming that it lacked educational value.

All of this was the predictable outcome of legislation passed by the governor in May that prohibits schools from teaching students that anyone is privileged or oppressed based on their race or skin color.

Somehow, many of the people who approve of this proposal, whose political leanings the Governor was almost certainly trying to appease with his legislation, are people who would most emphatically claim to revere the Bible. They will argue that it’s pointless to acknowledge and repent of the sins of the past. That the Bible says we’re responsible only for our own sins.

I’m reminded of Nehemiah, whose work reconstructing the walls of Jerusalem began with repentance for the past. Not a past he had direct part in, mind you. Still, he mourns, he fasts, and then he prays:

“I confess the sins we Israelites, including myself and my father’s family, have committed against you. We have acted very wickedly toward you. We have not obeyed the commands, decrees and laws you gave your servant Moses.”

Nehemiah includes himself and his father’s family in the sin that led to the disaster of the Babylonian Exile. He includes himself among those previous generations who “acted very wickedly” toward God. He includes himself, no doubt, because he feels his own sin. But also because the sins of his ancestors had marked his own generation. He intends to be in the vanguard of a new movement back to God, back to faithfulness, justice, righteousness, and holiness. He takes it upon himself to begin his people’s return to God by taking responsibility for the past.

The American church has often insisted that returning to God means calling out the sins of other people and gaining power for ourselves and those with our “values.” We should take another look at Nehemiah. If we only find that Scripture justifies ourselves and demonizes other people, if we aren’t confronted by our own sin in its pages, we aren’t reading it right. If we really want to return to God, it requires that we take responsibility for the past. Not to wallow in guilt, but to recognize the pervasiveness of sin, selfishness, and injustice. Otherwise, we’re doomed to the same failures as those who came before us. Their unnamed sins will ensnare us too.

But it’s more than that. The sin of slavery still marks our world. Black families have been stripped of their history and names. Generational wealth has been stolen. Racism still exists, long after enslaved people were emancipated in America. If we can’t show our children that we recognize and are sorry for the sins of our shared history, how can we assure them that we won’t repeat them?

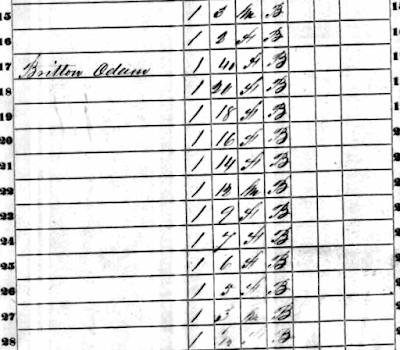

I said Stacie Marshall’s story was personal. My great-great-great grandfather, Britton Odum, established a multi-generational family farm in Middle Tennessee after he received a land grant for fighting in the War of 1812. He died on December 15, 1862, two months after the Emancipation Proclamation. I have a document similar to the one Stacie found, except the one I have lists 12 enslaved people: 2 adults, 3 teenagers, 7 children.

I wish that wasn’t true. We all want to idealize our families, I guess. But my family is marked by the sin of slavery. Succeeding generations of Odums, including me and my son, have benefitted from the work of those enslaved human beings. I don’t know their names, if they had descendants, or what became of them.

I can close the drawer on that sin. Or I can acknowledge and repent of it. It doesn’t invalidate my whole family history, of course not. But it marks it. And I owe it to those 12 human beings to feel sorrow, to wish it were not so, and to repent of that sin on behalf of those who cannot, but who I hope would if confronted with it. I owe it to my son. And I owe it to people in my life whose own families were touched by its evil.

God can take even a horror like slavery and redeem it. With his grace, I can choose a different legacy to leave behind: one of love, acceptance, and reconciliation. As Stacie said, that’s something I’ll have to live out for the rest of my life. It won’t ever be truly finished. It’ll take lots of different forms, and demand along the way that I repent of other sins, no doubt.

As God’s people, we’ll never make a difference in the world as long as we think that the way back to him is amnesia about the past and judgment turned outward on the sins of other people. But if we’ll accept our own sins, including those of our ancestors, and commit to a different legacy, God will honor and bless that.

No comments:

Post a Comment