For the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart. (Hebrews 4:12, NIV)

My family and I like trivia. We may or may not have once put together a week-long reign of terror over a cruise ship’s trivia competitions to the extent that late in the week other contestants just shook their heads and looked dispirited when they saw us come in. (Pro tip: If you don’t drink on a cruise ship, you’ll have an advantage in the trivia competitions.)

Since we like trivia, we like watching Jeopardy. Last week we were watching the Tournament of Champions. If you’ve never watched the TOC, the first thing you have to know is that the clues are hard: much harder than normal Jeopardy. Seriously, they’ll make you feel bad about yourself.

So I was excited when the Final Jeopardy category one night was “The New Testament.” I don’t know everything about the Bible, but I’m 95% sure that I’ll know the answer to Jeopardy Bible clues. Even during the TOC. That’s kind of my wheelhouse. So I was feeling good about it.

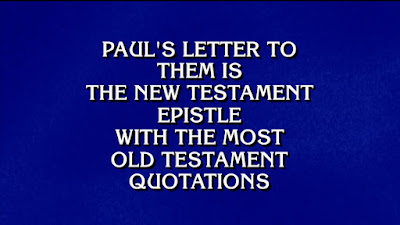

The clue was: “Paul’s letter to them is the New Testament epistle with the most Old Testament quotations.”

Now, the correct response to that clue is, “Who are the Romans?” Sam Buttrey answered correctly. Amy Schneider and Andrew He both responded with, “Who are the Hebrews?” Sam’s response, though, was ruled incorrect, while Amy’s and Andrew’s was accepted.

Jeopardy got it wrong. It’s true that Hebrews contains more Old Testament quotes than Romans, but almost no New Testament scholar today would tell you that Paul wrote Hebrews. If you turn to Hebrews in the King James Version, you’ll find that it’s titled “The Epistle of Paul to the Hebrews.” That was Jeopardy’s explanation; they use the King James Version. Book titles, however, have never been part of the original text of the Bible, either Testament. And if you happen to have access to a 1611 King James Version, you’ll find that at the end of Hebrews is a line that reads, “Written to the Hebrewes, from Italy, by Timothie.” It’s been dropped out of more modern versions of the KJV because you can’t find a manuscript earlier than the 5th century that includes it.

The book itself doesn't make an authorship claim. There is an ancient tradition that Paul wrote it. Many of the oldest Greek and Latin manuscripts and versions that have collections of Paul’s letters include Hebrews — at least three from the fourth or fifth century have it between the letters to Thessalonica and the letters to Timothy. But authorship was disputed even then. Paul’s involvement became important because the Western church debated whether to include Hebrews in the canon, in apostolic authorship was a criterion. It doesn’t seem to have been until the 5th century, about 400 years after it was written, that Paul’s authorship was taken as anything like a settled fact. And even then it wasn’t unanimous and was based on some pretty thin evidence.

Others have been speculated to have written the book: Barnabas, Clement of Rome, Luke, Apollos, even Priscilla, though no solid case has been built for any of those. Still, for the last 150-200 years, the letter’s anonymity, prominent style and vocabulary differences between it and Paul’s letters, and the difficulty of explaining why Paul’s name would have been removed if it had ever been attached have convinced the vast majority of scholars that Paul is not the author of Hebrews.

None of that matters a whole lot, though; Hebrews has encouraged, challenged, and strengthened generations of believers before us. Its authorship likely doesn’t make much difference to you — unless, of course, it costs you a chance to win a quarter of a million dollars on a TV game show. It’s just interesting. Bible trivia, if you will.

I started thinking, though, after Sam lost the game with what was almost certainly the correct response: What do I take for granted about the Bible that just isn’t true? And is it less trivial than a Jeopardy answer?

That’s obviously a hard question to answer; if I’m taking anything for granted, it’s probably not at the level of conscious thought that allows me to rationally consider it on my own. I do know that there were things I once believed the Bible said that I now don’t think it says. Things that I was once convinced of that I wouldn’t be able to affirm anymore. Sometimes that was because I misunderstood. Other times, it was because I just sort of took for granted something someone else said, without really considering it for myself. Given what I’ve done for almost 30 years, that’s likely caused me to mislead others. Maybe to get in the way of the gospel, even. When you preach and teach the Bible every week, you can’t afford to do that — that’s why James says those who teach are to be held to a higher standard.

I’ve also seen the tendency in others enough to know that I’m far from alone. I’ve seen people who, confronted by reasons to question their point of view about a Bible text or a belief, refused to consider that they may have been wrong. We all misunderstand Scripture at times. All of us misread it. But if the Bible in some way forms who we are, we have to let it speak to us. We can’t afford to mute it with our prejudices, our dogmas, our need to justify ourselves. We have to allow some uncertainty as Scripture, through the work of the Holy Spirit, does its work of judging the thoughts and attitudes of our hearts. We have to be able to admit it when the answers we think we have are wrong and when we need to back up and let Scripture have its way with us.

And before we protest that our answers aren’t wrong, we need a dose of humility. Can’t you name some ways in which previous generations of believers got the Bible wrong? Using it to justify slavery, or segregation? To subjugate women? To choke off legitimate dissent against totalitarian governments? To defend a geo-centric model of the universe? Scripture has been used to perpetrate terror campaigns against Jews, Muslims, and homosexuals. It’s been used to defend and cover up ungodly behavior. It’s been used to draw unbiblical lines between well-intended followers of Jesus.

They got the Bible wrong. At least parts of it. Some were convinced they were right, and they got it wrong. They were good Christians, many of them, respected and loved by everyone, and they got it wrong.

Isn’t it just possible that some of the Bible answers we come up with might be wrong, too? Even the ones passed down from the people we love and admire the most? “We’ve always believed that” isn’t the same as being right, not if the Bible really is alive and active. That makes it less a code chiseled in stone and more a live organism that wants always to do its work in our hearts, now. It’s not a collection of trivia to be memorized and regurgitated. Like the game show, its answers are often about knowing how to ask the right questions.

One of the ways we avoid getting stuck in our own little understanding of the Bible is by reading it with others — preferably people as different from you as possible. With all the resources at our disposal, there’s no excuse for reading the Bible in a little personal devotional bubble. That might shake you a little. You won’t always agree. But it will keep you from getting locked into your own reading and understanding of Scripture.

There’s nothing trivial about growing in your knowledge of Scripture. Don’t take it for granted. Let its sharp edges cut you where necessary. And don’t be afraid to find your answers in the questions it raises.

Even — especially — about things you thought you already knew.

This is so well-written, Pat. You have nailed it! You really got me thinking when you suggested that we should be careful about Bible-reading in our own little bubble. Thanks for another thought-provoking post. Laura (Deckard) Sande

ReplyDelete